Scotland’s ‘Demographic Timebomb’

Written by Cameron Boyle on 28 August 2020

Scotland’s ‘Demographic Timebomb’: Can Immigration Provide The Solution? By Cameron Boyle

Scotland’s demographic structure is changing. The birth rate is falling, the population is ageing and population growth is stagnating. When these factors are combined, the end product is a working-age population that is too small to meet the needs of the labour market. That is a demographic timebomb.

Increased immigration can help to solve these issues. Migrants’ younger age profile means they are well-placed to enter the labour market and redress the demographic imbalance. Yet with the current devolved setup preventing Scotland from crafting its own immigration policy, it is important to assess what the future holds.

The impact on the labour market

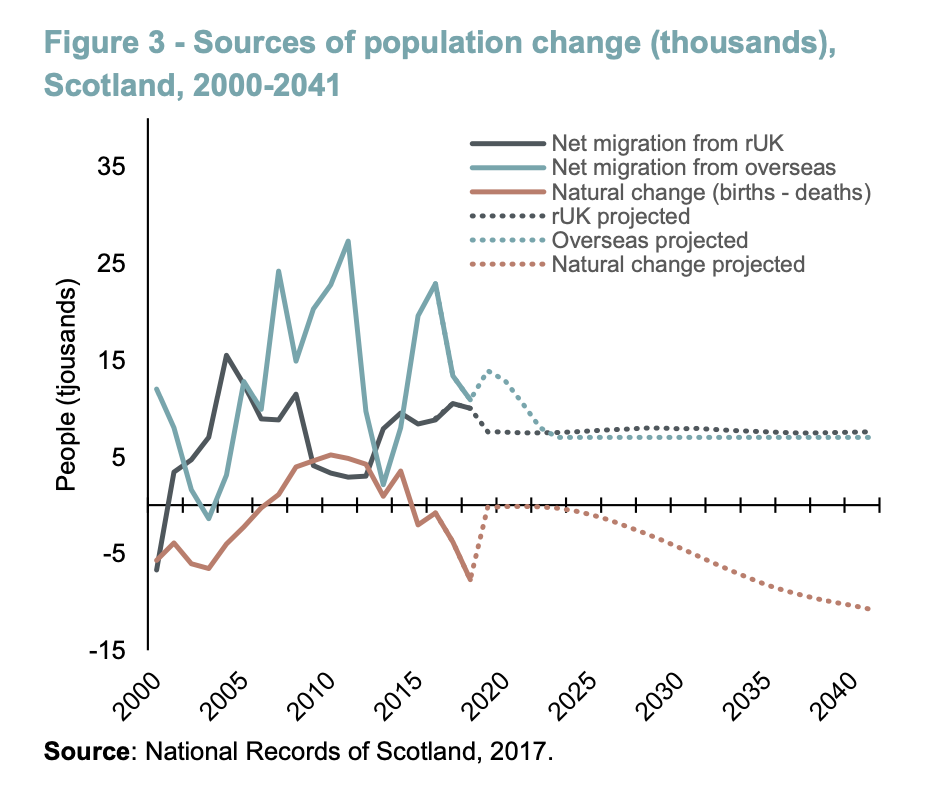

By 2041, Scotland’s pension-age population is expected to have risen by around 265,000, with the working-age population set to rise by just 38,000. And these shifts hold considerable implications for the health of the labour market and for the economy as a whole. An abundance of elderly citizens increases what’s known as the ‘dependency ratio’- a measure of the number of dependents in an economy (persons aged zero to 14 and over the age of 65) compared with the total working-age population.

A high dependency ratio is economically problematic for a number of reasons. Not only are elderly citizens unable to work, they place increased pressure on the labour market, particularly within sectors such as health and social care. With the ever-increasing number of pension-age citizens showing no signs of slowing, and Scotland’s dwindling birth rate failing to provide a demographic counterbalance, the defining challenge of the future will be a shortage of workers.

As touched upon, immigration is a way of rising to this challenge. It can provide a steady stream of working-age citizens into the labour market, enabling skills gaps to be filled and the impact of an ageing population to be mitigated. Yet with migration into Scotland predicted to sharply decline until 2023- after which point it is projected to remain at a constant but lower level than the rest of the UK- the influx of people from overseas is not set to form the demographic solution that Scotland needs.

Taking all this into account, the need for a new approach to immigration in Scotland could not be clearer. The UK’s one-size-fits-all approach is failing to address Scotland’s unique demographic and economic challenges, and this failure is set to intensify when participation in EU freedom of movement ends and the new points-based immigration system comes into effect.

A system must be developed that ensures that Scotland has access to adequate numbers of working-age citizens. If this cannot be achieved, future economic prosperity is under threat. Regrettably, the current devolved setup leaves control over immigration policy concentrated in the hands of the Westminster government, who thus far have been intransigent in their opposition to providing Holyrood with greater flexibility in his area.

Plans for a Scottish Visa

In an attempt to defuse what has been described as the ‘demographic timebomb’ with the limited powers available, the Scottish Government announced plans for a ‘Scottish Visa’; a tailored migration system aimed at giving Scotland access to the people it needs in order to flourish.

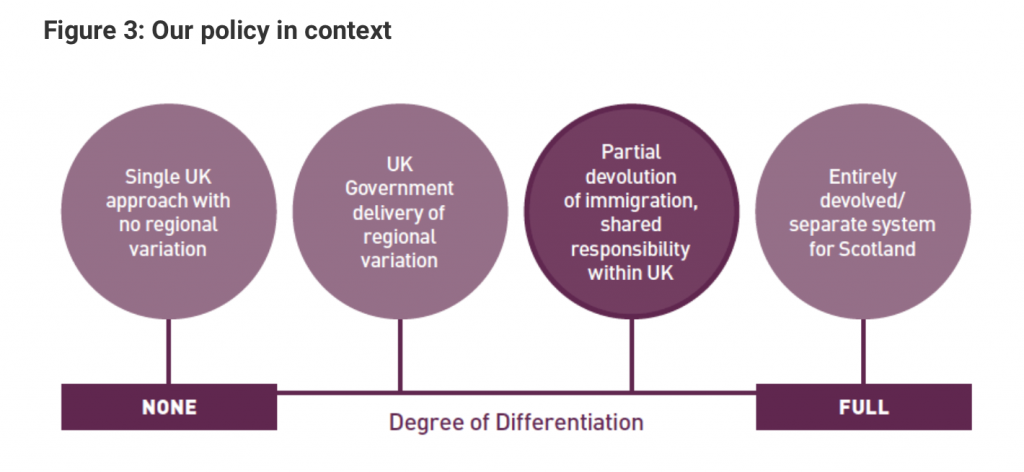

The proposals are designed to work in accordance with the current devolved relationship between Holyrood and Westminster, but the ‘principles and practical measures’ could be adapted for a fully independent Scotland were this to become a reality in the future. The visa would see control over immigration policy split between the UK and Scottish governments; overseas nationals intending to relocate to Scotland could apply for either a Scottish Visa or one of the existing UK immigration routes.

The granting of a Scottish Visa would be contingent on the applicant living in Scotland and possessing a Scottish tax code- this would ensure that Scotland benefited both demographically and economically from the introduction of the new immigration route. The Scottish Government has set out the various ways that the visa could be structured here and in a policy document entitled ‘Migration: Helping Scotland Prosper’.

Under one model, the Scottish Government, accountable to the Scottish Parliament, would be responsible for the new visa’s eligibility requirements, enabling them to be crafted in line with Scotland’s demographic and economic objectives. The Scottish Government would then receive and assess applications before nominating successful applicants to the UK government so that the necessary security checks could be conducted.

Regarding the proposals, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon had this to say:

‘Migration is an issue which is crucial for our future, but the Scottish Government doesn’t currently have the powers needed to deliver tailored immigration policies for Scotland.

Devolving immigration powers by introducing a Scottish Visa would allow Scotland to attract and retain people with the skills and attributes we need for our communities and economy to flourish.’

Plans for a Scottish Visa

Somewhat unsurprisingly, the plans were rejected by Westminster quicker than it would have taken to read them through.

Lessons from overseas

The SNP has long made the point that Scotland could benefit from looking to the positive economic examples set by other small countries, such as Ireland, Finland and Denmark. In 2018, the Sustainable Growth Commission published a report entitled ‘Scotland: The new case for optimism’, which sets out the steps Scotland must take in order to emulate the economic growth of such nations.

One such step involves being ‘migration friendly’. Due to Scotland’s demographic structure, migration is critical not only in terms of population growth but also productivity performance. According to the IMF, a 1 percent increase in the share of migrants in the adult population can increase productivity by 3 percent in the long run.

Therefore, increasing levels of inward migration is key to economic growth. Taking the Republic of Ireland as an example, immigration was a driving force behind the population increase of 24 percent that occurred between 1999 and 2015, a process that in turn played a pivotal role in Ireland’s economic resurgence.

What does the future hold?

With Scotland removed from the EU against its will, and resultantly set for a sharp decline in EU migration, it is difficult to see how the impending demographic issues can be addressed unless there is a substantial change of policy.

Just over 7 percent of employment in Scotland comprises non-UK nationals, 71 percent of whom come from EU member states. Within certain sectors such as manufacturing and distribution, hotels and restaurants, EU migrants form upwards of 8 percent of the overall workforce, more than four percentage points greater than their share of the overall population. When Scotland’s wider demographic trends are factored into this, there are serious question marks over the future prosperity of these industries.

Working towards a greater level of autonomy is the only way forward. At present, Scotland has no choice but to accept an immigration system that fails to address its demographic needs. Despite the intransigence of Westminster, further devolution or full-scale independence appears the only route out of the current quandary.

Cameron Boyle is a political correspondent for the Immigration Advice Service, an organisation of immigration lawyers with offices in the UK and Ireland.